Crime, gender-based violence and grief

As student journalists enter the professional field, taking on a reporting beat involving crime or violence can quickly shatter illusions. The situations they confront aren't like the hit show, "Law and Order: Special Victims Unit," where the case is wrapped up in a bow. There is no screen separating the viewer from reality. Reporters are both the witness and the storyteller in delivering the news. How can students build the resilience to cope?

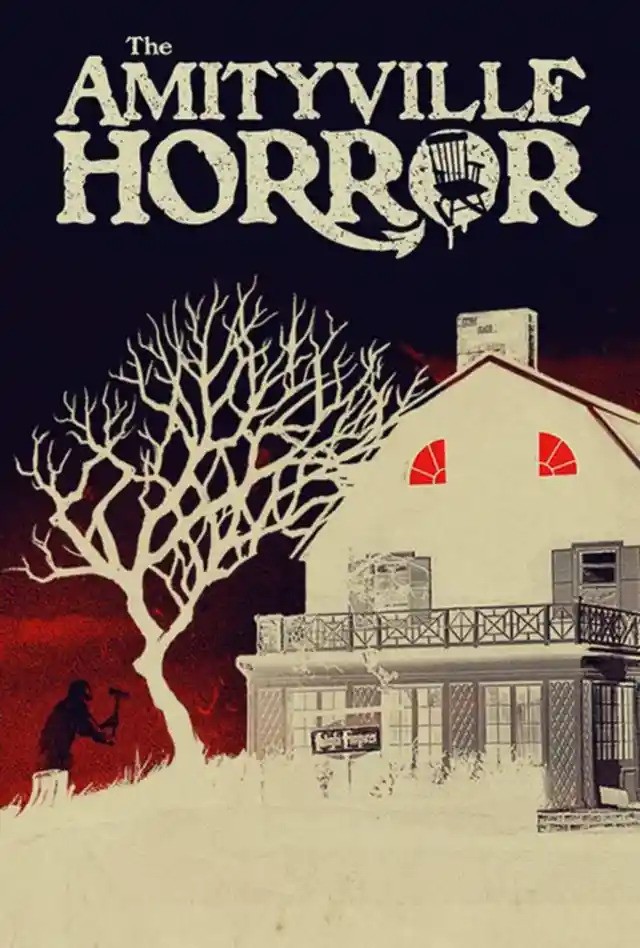

Carolyn James, the publisher of the Amityville Record, is often approached by entertainment executives hungry for information about the sensationalized murders of six members of the DeFeo family in Amityville in 1974. The incident spawned a series of supernatural horror movies and a torrent of interest that continues to this day. James makes it a priority to set her own boundaries and declines to assist projects that she believes contribute towards the exploitation of the deceased.

"This was a tragic event. A young man killed his entire family. My readers were their neighbors, their cub scout leaders, their girl scout leaders, their coaches, in school their teachers and they don't want to see another story about a ghost or haunting. So we cannot be part of that."

Caroline James, owner of the Amityville Record, New York

There are moments when reporters have to steel themselves to hear or view extremely distressing content. On her first day as a journalist, Elaine Aradillas, a former senior crime reporter for The Messenger and People magazine, was dispatched to the scene of a horrific motorcycle accident.

"I remember I had so much anxiety because I didn't know what to expect. Was I going to see a dead body? I saw the police officers in the grassy median and I'm like, 'What are they doing?' And the officer tells me that they're looking for the helmet because the head of the victim is still inside."

Elaine Aradillas, former senior reporter for The Messenger and People Magazine

Journalists are frequently tasked with interviewing survivors and their families. Navigating stories that involve violence, grief or bereavement requires a high level of professionalism, empathy and tact. Yet the more capable you are, the more likely you are to be exposed to similar beats. "Because I got people to open up to me all the time, I was put in more difficult, more stressful, more traumatic situations," Aradillas said.

Reporting on harrowing issues, such as gender-based violence, can have an negative impact on journalists' mental health, which sometimes emerges only months or years later. Lucy Westcott, emergencies director of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), recalled how a reporter who investigated sexual abuse in a community came to her organization six months' later in great distress. She was struggling because of the stories she had heard, but also because her interviewees were still leaning on her for support.

"It can be very, very difficult to feel you're a journalist and you're there to do one job, but your sources are relying on you for more than that."

Lucy Westcott, Emergencies Director, Committee to Protect Journalists

In response, the CPJ was able to provide the reporter with a grant towards counseling, but the cost of therapy and care can be prohibitive for journalists. Westcott emphasizes that interviewing survivors ethically and providing them with contact information for support organizations can help alleviate trauma for journalists and their sources.

Eden Fineday, a Nehiyaw Iskwew (Cree woman) from the Sweetgrass First Nation and publisher at IndigiNews, Canada, has covered police violence, murders, and missing indigenous women, and is herself a survivor of intergenerational trauma. She urges reporters to avoid sensationalism.

"Try to focus on people's humanity. If you take a moment to understand what they're saying . . . it means that you're talking about someone as a human being before calling them a victim."

Eden Fineday, publisher, IndigiNews, Canada

Be mindful of language and framing when reporting on crimes such as gender-based violence or sexual assault. Avoid sensationalizing or romanticizing abusive behavior, as this can perpetuate harmful stereotypes and further stigmatize survivors. Use accurate terminology and provide context to help readers understand the complexities of the story without resorting to graphic details. If you are reporting on suicide, the AP Stylebook and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention provide useful guidelines.

Additionally, consider the broader societal implications of trauma in your reporting. Highlight systemic barriers and inequalities that contribute to violence against marginalized communities. By contextualizing individual experiences within larger social structures, you can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.

When interviewing survivors, it is crucial to avoid re-traumatizing them by asking intrusive or triggering questions. Instead, create a safe space for survivors to share their experiences at their own pace. Active listening and validation of their emotions can help foster trust and openness.

For further information, see our guide to trauma-informed reporting in the section on "Coping Strategies".