Exterior Frame Wall-to-Foundation Wall

At the base of the frame wall, the water control layer of the wall must terminate in a way that directs water away from the building. The air control layer is transitioned either to the foundation wall (in the case of a flat foundation wall such as a cast concrete foundation wall) or to the framing sill (in the case of an irregular surface foundation wall such as one constructed of field stone or split block).

The transition details for the base of the wall are largely independent of the treatment to the inside of the foundation wall. The transition details are impacted by whether the wall air control layer is fully-adhered or non-fully- adhered. In the case of a frame wall-to-foundation wall transition where the base of the wall must promote drying to the exterior, the transition details are most impacted by whether or not the air control layer of the wall is vapor permeable.

Note that the frame wall-to-foundation wall transition is where "critter control" is important.

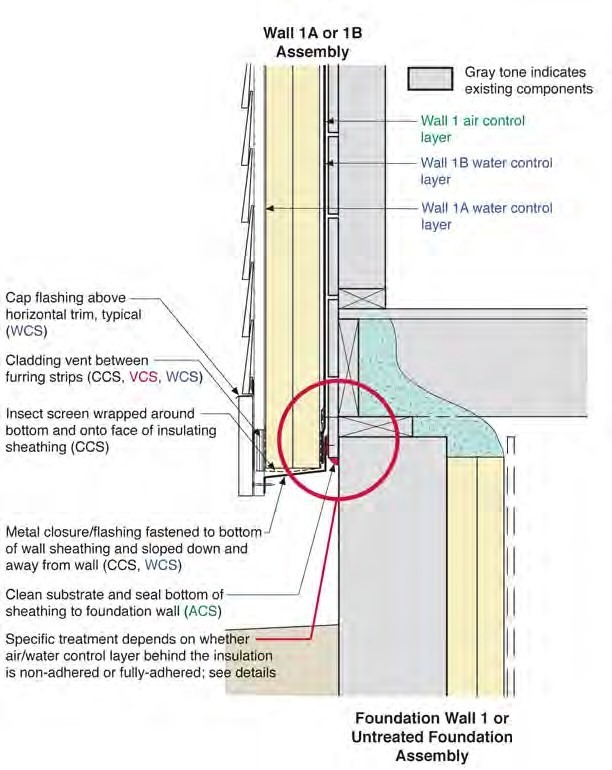

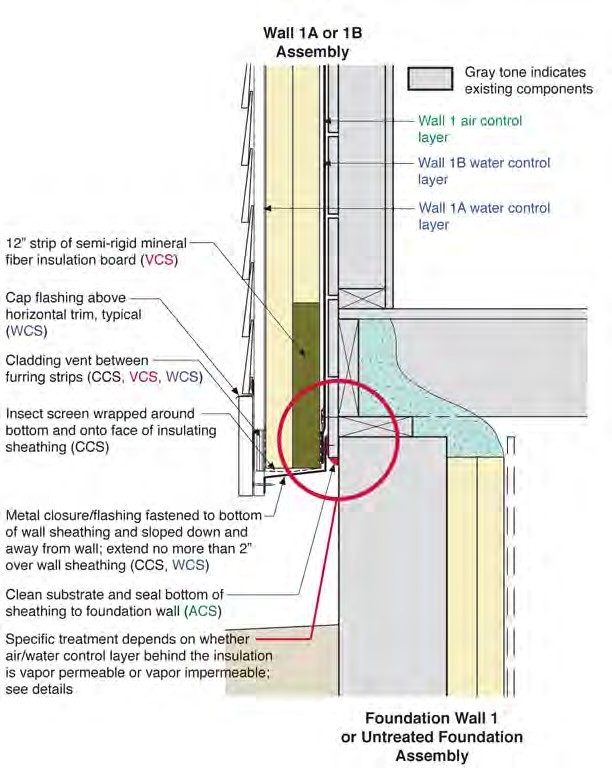

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 1 or Untreated Flat Foundation Wall

- This transition drawing applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

- Protection of the above-grade wall structure from termites relies upon a clear separa- tion distance between the ground and the wall structure.

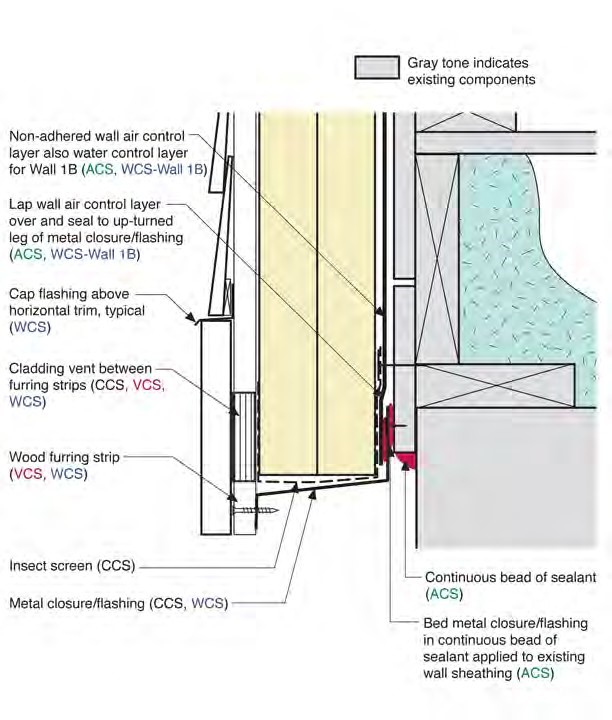

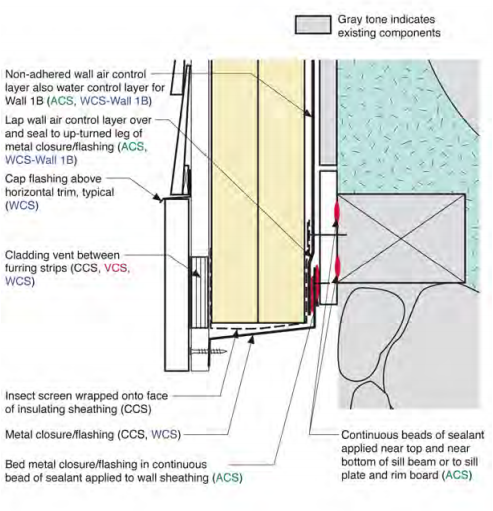

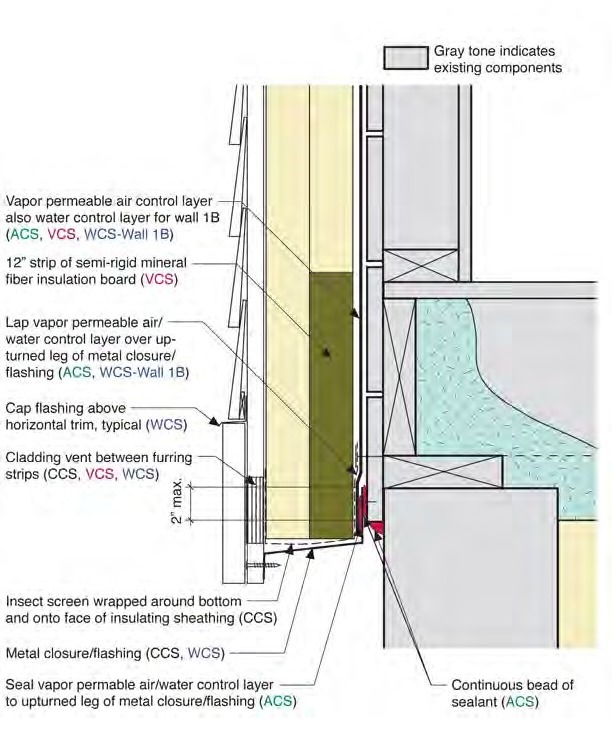

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 1 or Untreated Flat Foundation Wall- Detail for Non-Adhered Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

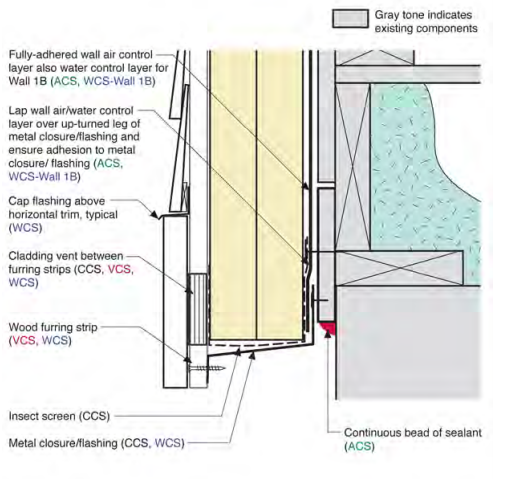

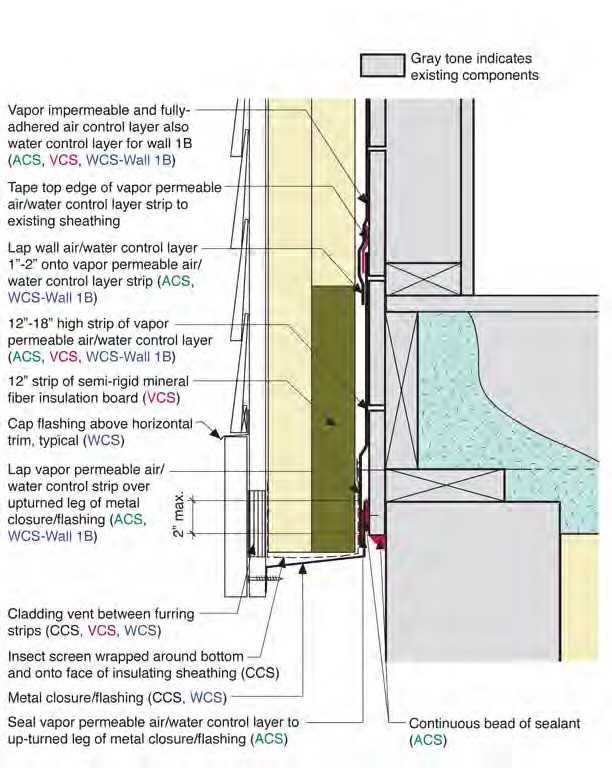

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 1 or Untreated Flat Foundation Wall- Detail for Fully-Adhered Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

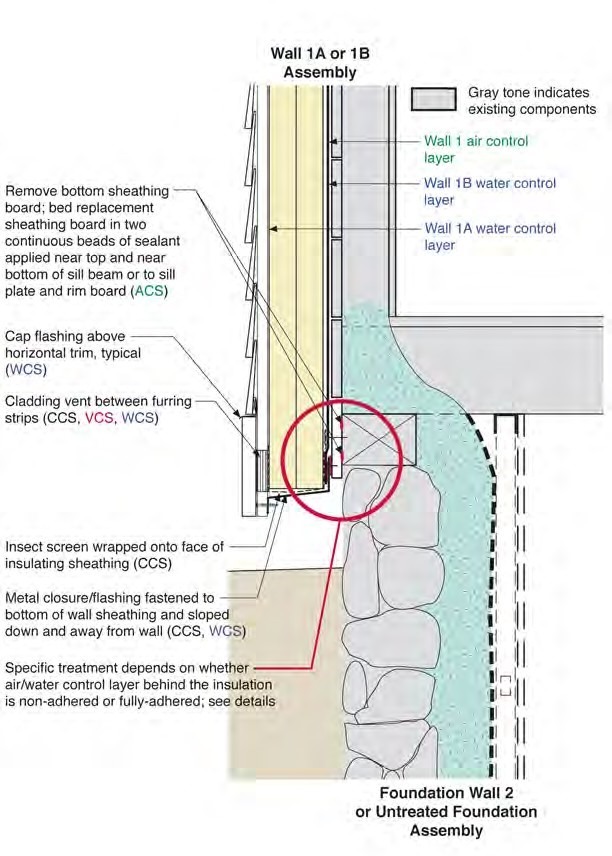

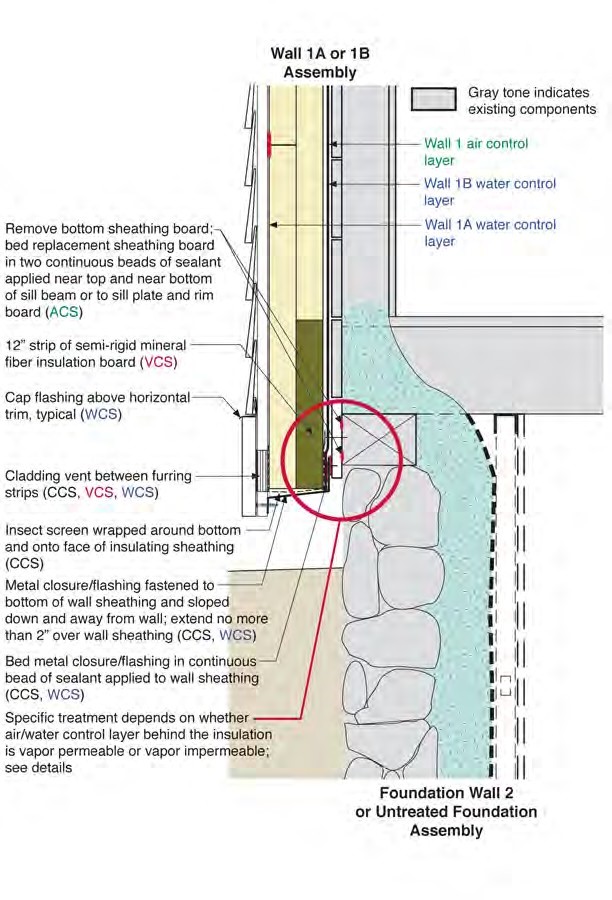

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 2 or Untreated Irregular Foundation Wall

- This transition drawing applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

- Protection of the above-grade wall structure from termites relies upon a clear separation distance between the ground and the wall structure

- The bottom sheathing board must be removed to provide air control transition from the retrofit foundation wall, through the sill, to the retrofit wall.

- When the bottom sheathing board is removed, inspect the sill for damage and repair/ replace as needed.

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 2 or Untreated Irregular Foundation Wall- Detail for Non-Adhered Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 2 or Untreated Irregular Foundation Wall- Detail for Fully-Adhered Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

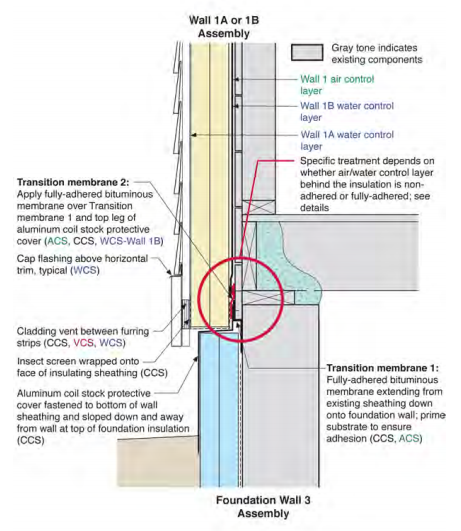

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 3

- This transition drawing applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

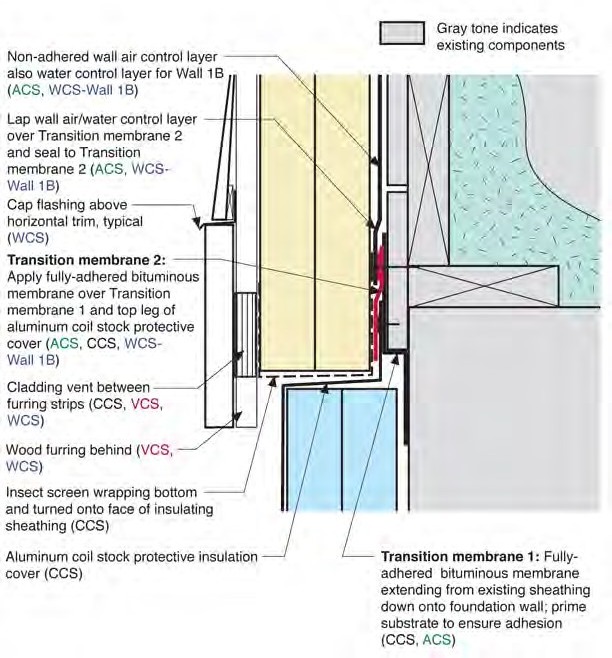

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 3- Detail for Non-Adhered Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

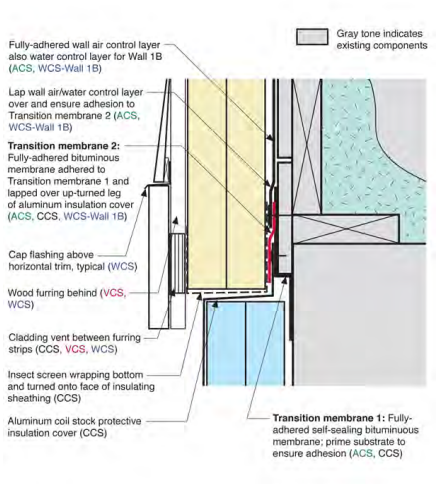

Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 3- Detail for Fully-Adhered Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

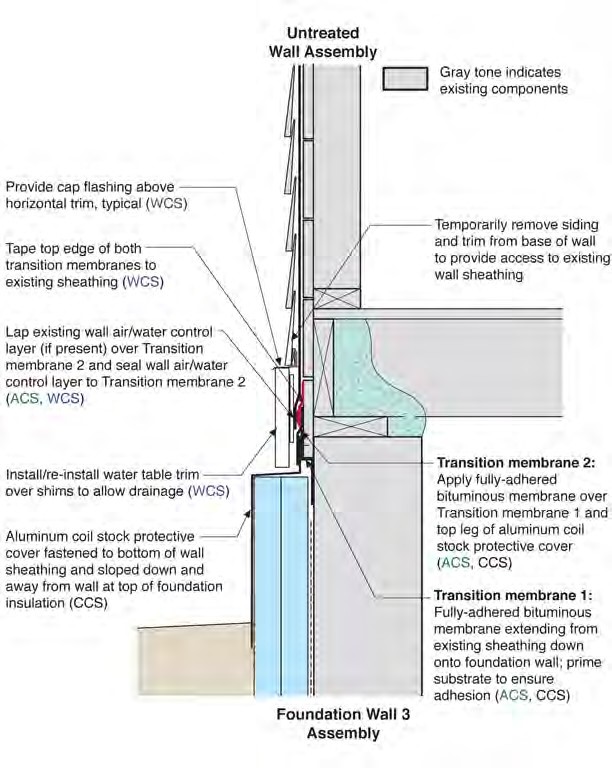

Untreated Wall to Foundation Wall 3

- Siding and trim at the base of the wall must be temporarily removed to access the base of the wall sheathing.

Special Case: Provide Drying for Framing Sill

The retrofit treatments of the foundation wall and of the framing sill tend to severely limit or eliminate the ability of the these components to dry to the inside. Foundation walls that are subject to capillary transfer of water (wicking) risk transferring moisture to framing that is on top of the foundation wall if there is no capillary break between the foundation and the framing and if the moisture is not able to dry out of the foundation wall before it reaches the framing. If moisture is transferred to the framing faster than the framing is able to dry, moisture will accumulate leading to decay.

Foundation walls that are subject to capillary transfer of water are 1) constructed of wicking materials such as, for example, concrete, concrete block, brick, sedimentary stone, significant proportions of mortar; and 2) in contact with liquid water such as in the form of ground water, surface water or incident rainwater.

Capillary moisture generally evaporates from the exterior surface of a foundation wall if the foundation wall has appreciable exposure above grade (e.g. height of the exposed exterior portion of wall is greater than 1 ½ times the thickness of the wall) and it is not covered by a layer or material that would inhibit drying (e.g. it is not covered with epoxy paint).

For more discussion of capillary moisture as it relates to the frame wall- foundation wall interface refer to the Building Enclosure Functions section in Part 1 of this guide or Building Science Insight-011: Capillarity-Small Sacrifices and Building Science Insight-041: Rubble Foundations both of which are available at www.buildingscience.com.

Moderate levels of moisture transfer to the framing might be managed by insulating the framing in a way that promotes drying to the exterior. If water can dry from the framing at a faster rate than water is wicked to the framing, then moisture will not accumulate. Below are details that demonstrate this approach for both flat and irregular surface foundation walls.

It must be noted that the methods presented below address moderate levels of risk. In situations where the capillary transfer of moisture through the foundation wall to the framing is significant, insertion of a capillary break and/or other measures will be necessary.

Drying for Sill: Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 1 or Untreated Flat Foundation Wall

- This transition drawing applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

Drying for Sill: Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 1 or Untreated Flat Foundation Wall-Detail for Vapor Permeable Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

Drying for Sill: Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 1 or Untreated Flat Foundation Wall-Detail for Vapor Impermeable Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

- The vapor permeable air control layer should extend up beyond the first floor framing.

Drying for Sill: Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 2 or Untreated Irregular Foundation Wall

- This transition applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

- The replacement sheathing board that is installed over the sill must be solid sawn wood and not OSB or plywood.

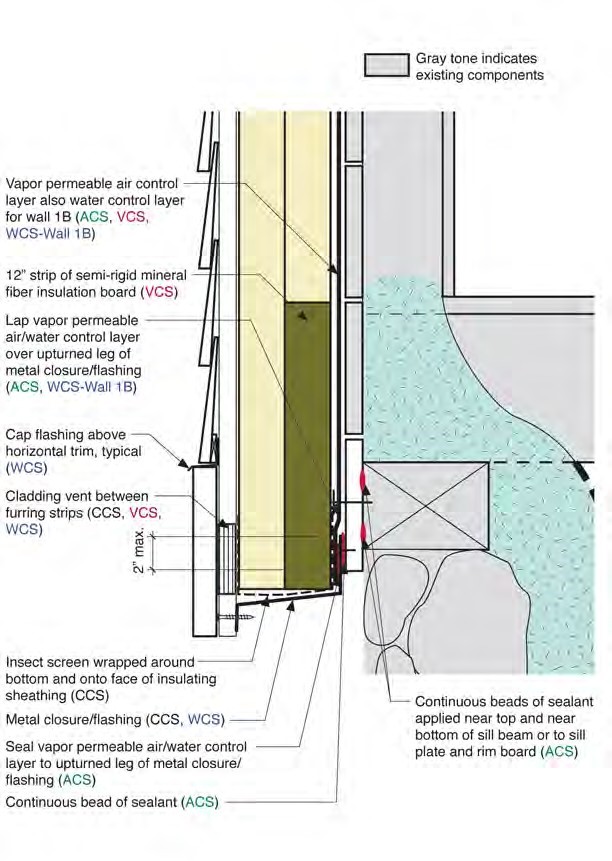

Drying for Sill: Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 2 or Untreated Irregular Foundation Wall-Detail for Vapor Permeable Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

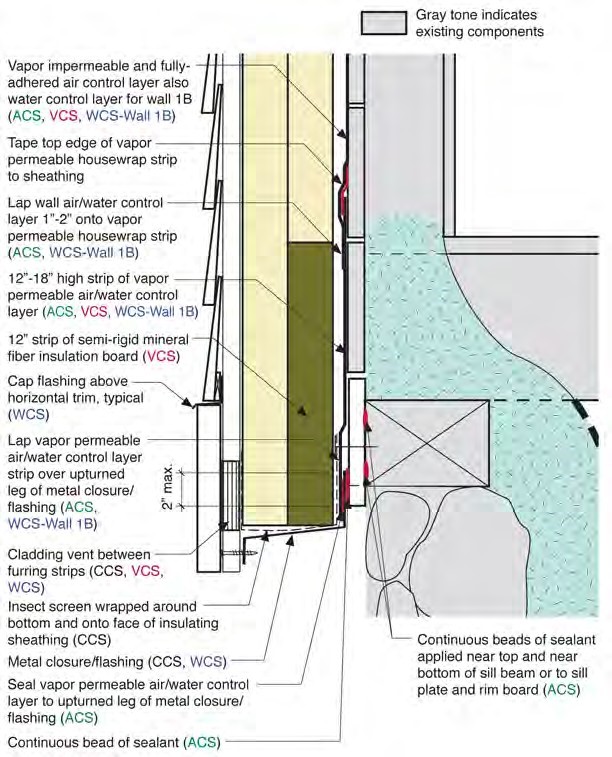

Drying for Sill: Wall 1 to Foundation Wall 2 or Untreated Irregular Foundation Wall -Detail for Vapor Impermeable Wall Air Control Layer

- This detail applies for Wall 1A and Wall 1B.

- The vapor permeable air control layer should extend up beyond the first floor framing.