Nir Eyal : The Psychology of Building Addictive Products

source - 2016

Can't stop using Facebook, Pinterest, and Snapchat? Here is why:

Originally written by David Landau to Startup Grind, the global entrepreneurship community

What are the patterns behind habit-forming technologies? Looking at Snapchat, Slack, and WhatsApp, we notice products that keep us checking, scrolling, and coming back for more. So how do they do it? Nir Eyal, an investor and entrepreneur with two sold companies under his belt, has spend 3 years of his life crystallizing an answer, and published it as "Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products" He presented his key findings at the Startup Grind Global Conference, pointing to distinct ways founders can leverage psychology into their businesses, all in the divine pursuit of daily active users.

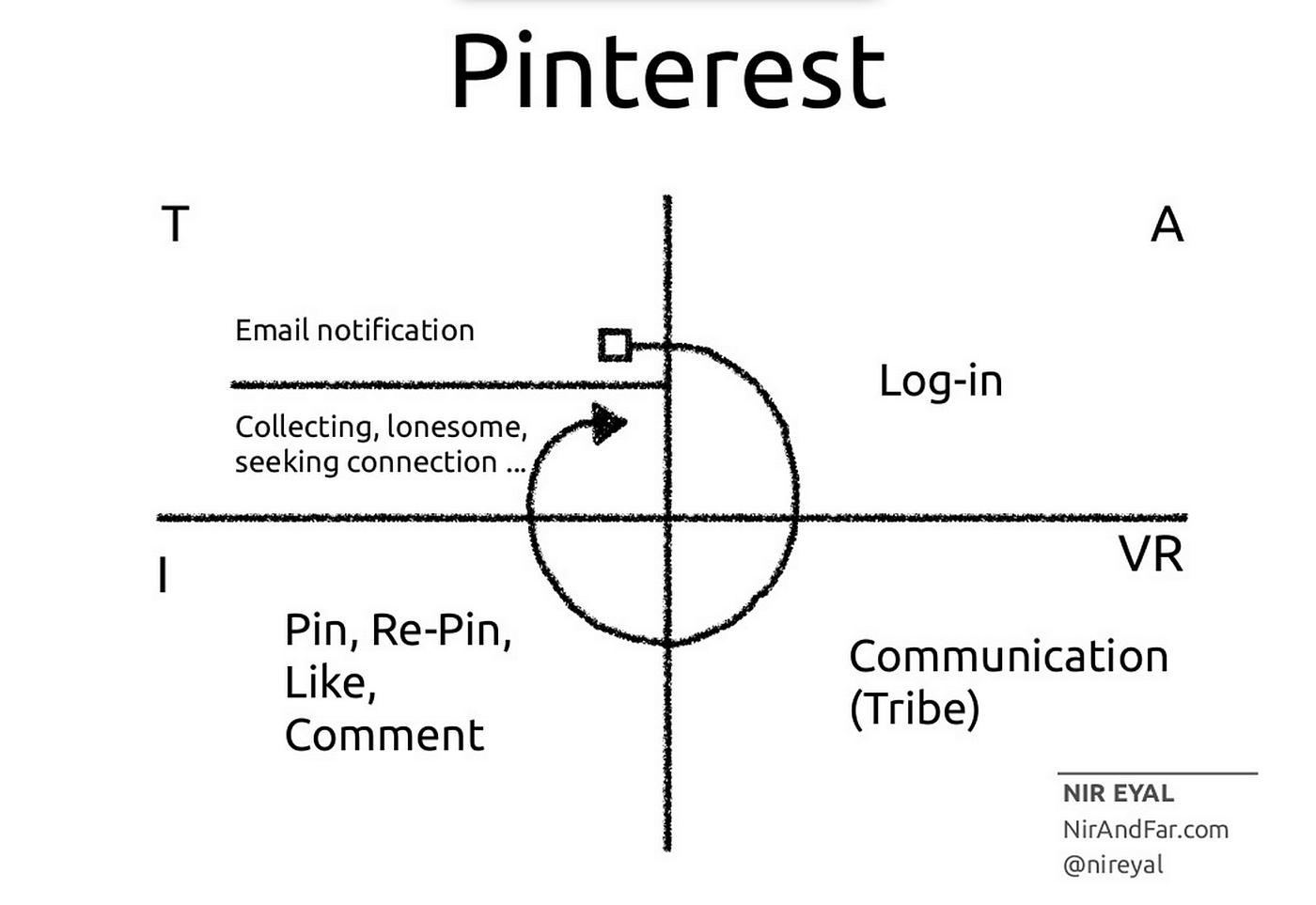

But first, what is a habit? "An impulse to act on a behavior with little or no conscious thought," posed Nir, adding that it's generally a quick, repetitive action - though different and distinct from tasks users must do to use your product, like fill out a profile. Good habits are things users want to do repeatedly like play YouTube videos, scroll through Instagram photos, or keep coming back to Zynga's Mafia Wars - all in order to fulfill emotional needs. Part of this is explained through Nir Eyal's Hook Canvas.

Nir Eyal's Quick Guide to Building Habit-Forming Products

- Emotion: What internal trigger is the product addressing?

- Feature: What external trigger gets the user to the product?

- Incentive: What is the simplest behavior in anticipation of a reward?

Most addictive companies start out as toys - "nice to haves," - and seem inconsequential. Who thought Facebook would be as big as it is today, back when it launched? But as they grow, they end up "touching 100,000,000s of users and making billions," says Nir.

The hooks - now nearly infinite - of Facebook are it's news feed, and to a lesser extent, the positive surprise of messages or seeing likes on posts. The same goes for Twitter, through likes and retweets. In comparison, social networks that are more static and have less novel activities are less likely to maintain hooks on users.

A great hook doesn't have to achieve anything concrete. The simpler, the better. It's an experience designed to influence a user to interact with your platform often enough to form a habit - and it's the core of any addictive company.

Nir believes we're at in an era where we can help people use these habits for good, and lead happier and more productive lives. However, users and entrepreneurs should be aware that - like any addiction - great hooks work regardless of the intent, or the results. "If it can't be used for evil, it's not a super power," quotes Nir.

The Psychology of Addictive Products

Every hook starts with two types of triggers: external and internal.

External Triggers tell you what to do next based on outside info. Think features like notifications, buttons, arrows reminding you to scroll, and more blunt techniques like the constant email reminders we love to hate.

Internal Triggers are more critical - and also ignored by most product designers. These are the true reasons that prompt us to action… but the information for what to do is not obvious digitally. Rather, Internal triggers are stored as associations inside the user's brain.

This isn't like the mind-manipulation seen in Inception, but rather the creation of irresistible user experiences. It's knowing how people feel, and what changes those feelings on a temporary and transient basis. Internal triggers work best when there's a persistent, recurring negative emotion; the trigger gives brief relief from that emotion, creating an addiction.

The simplest behaviors in anticipation of a reward:

- A Pinterest scroll, which might turn up an interesting photo.

- A Google search, which might teach us something new.

- A Play button on YouTube, which can capture our interest for a few minutes.

- All of these are simple actions tied to an immediate reward.

- The strongest triggers, Nir says, are when we feel "Bored, lonely, confused, fearful, lost or indecisive."

These, statistically, inspire the most action. Slot machines, anyone?

Is Depression the Best Teacher?

Nir cited studies like those of Sriram Chellappan, who showed unique traffic patterns in how depressed people surf the web. Other studies found that social media usage creates anxiety, leading us to ask: are the platforms with the best hooks both creating the need, and giving relief?

If so, that's genius… and also terrifying.

Nir believes we can understand this phenomenon by what psychologists call "More valent states." They feel down more often than most of the population. They check email to get out of that state.

If we're honest with ourselves, we all use products to modulate our mood: when someone's feeling lonely, they check Facebook; when someone's feeling unsure, they go to Google; when bored, people check YouTube, sports scores, news, and Pinterest.

All of these solutions take us from the unpleasant situation of boredom and give us relief. Before the emotion becomes conscious, the behavior is already occurring. Indeed, the lack of conscious awareness is key to sustaining a hook.

If you primarily check Pinterest when you're bored, what happens if you, through, say, meditation or therapy, reduce your overall negative emotions? Will you cut out your Pintrest use?

Not likely, if Pinterest's hook is working right.

When Nir consults and asks, "What's the psychological need of the product?" he said most founders don't know. To achieve scale scale, "You need to absolutely understand the emotional trigger in your user's life."

Case Study: Instagram

Instagram's external triggers are easy to spot: "Check out my photo on Instagram."

To help the audience understand Instagram's internal triggers, Nir asked an audience member about the last photo she took. "The beach," she said.

Why take that photo? The beach was so beautiful, the experience so precious, that underlying the action, Nir asserted, was an internal fear of losing the moment. Instagram catered to that fear, relieving it by capturing it.

The good: Here's a clear victory behind helping people experience more positive emotions.

The bad: Once you believe a digital action can make you feel better, you might ignore the bigger picture.

The ugly: That bigger picture might be soaking in the experience deeply, allowing it to change you - or looking at your life and perceptions of it, getting to the deep psychological root of why the fear arose in the first place. Instagram can only help a small amount here, and the results are fleeting. While apps with great hooks can give us relief, psychologically, they only medicate a symptom - not cure it.

This leads to an interesting ethical dilemma: To make a truly effective hook, we have to capitalize on users' negative emotions. To keep them using the product, their negative emotions (and thus the need relief) need to stick around.

The more we use Instagram's hook, the more we attach it to other internal triggers, whether fear, boredom, or the fear of missing out. The solution to that discomfort is found with this app in our pocket. The more we use Instagram, the more we associate it with more triggers, thus inspiring us to want to use it more.

This helps apps Instagram because it makes us want to find emotional release from multiple sources. If we suddenly become fearless, we'd still log in to find relief.

Creating the Formula for Getting Hooked

For any human behavior, Nir says, Behaviors = Motivation + Ability + Trigger

So how, as founders and product designers, increase the odds that our app becomes a behavior? By increasing the variables, naturally.

Increasing Motivation: 6 Tactics to Make Your App Addictive

Think about how you can introduce these motivators into your product:

1. Seeking pleasure.

2. Avoiding pain

3. Seeking hope

4. Avoiding fear

5. Seeking acceptance

6. Avoiding rejection

Every piece of marketing copy uses at least one of these six core motivations, thus making the triggered behavior more likely to occur.

Nir revealed "Companies with great hooks often don't look to the 20th century model of advertising. Facebook and Slack didn't advertise in the Superbowl. The ads don't bring people in; the experiences themselves create habits," which are far more powerful, and far more valuable.

Increasing Ability: Lowering Barriers to Addicting Behaviors

A click or scroll is incredibly easy and fast, thus more or less likely to occur.

Complicated and expensive actions increase the activation cost of a behavior, and make it harder to understand, thus less likely to occur. If you can do something simply, quickly, and cheaply, without complex thought, you're more likely to do it again, and again, and again…

When a user has enough motivation and ability, and is presented with the trigger when a motivation is present, it often succeeds - but it cannot be so challenging that it demands more motivation than the user has. When motivation is too low and ability requirements are too high, the trigger fails. The solution, then, is to remove obstacle in your customer's way: maybe that means eliminating the "first name, last name" fields in your email capture, taking out a step in your product purchase process, or placing a shortcut to the desired action in a more visible location.

"All technology is about shortening the distance between the recognition of the need and the reward."

Triggers & Rewards: Make Acting Valuable, but Unpredictable

In habit forming products, there's mystery, variability and uncertainty on what you might find when you use a product. When you scroll through images on Pinterest or updates on Facebook, you know you'll get something - but you don't know exactly what, or when.

Nir highlighted behavioral psychologist BF Skinner and discussed examples of pigeons pecking at a disk to get food. Instead of getting food at every single peck (predictable), Skinner found something else: the rate of response - the number of times pigeons pecked at the disk - increased when the reward happened at a variable schedule of reinforcement. That is, almost randomly.

The point of variable rewards is to give users what they came for. Scratch the user's itch, and leave them wanting more - but don't reveal your hand to let them know how far between they are between rewards, like with drops of good equipment in video games.

We may, as the masses, seem like easy to fool creatures, but by studying what forms and maintains habits - along with what can break them - we can often learn more about ourselves at the deepest level. Want to master your own habits? Then read Hooked deeply, and prepare yourself against the onslaught on your attention by knowing their tricks.